3 March 2009

When I arrived at the Staines small public dock in mid-June 2008 I could see the Thames was unusually high. The level of the river was only three inches below the top of the dock and I was amused that the gunnel of my kayak rose over its edge like a ‘real boat’. Normally the waterline washes about three feet below the dock and entering the kayak over its edge requires a ballet-like combination of precision, balance and nerve. And once seated, getting the gear that isn’t already strapped to the stern of the boat on board, (camera, maps, Ortlieb bag, water bottle, paddle), from overhead, while preventing the boat from wandering beneath the dock, is an unwieldy pantomime at best. At high water clambering aboard was a doddle.

The power of the river revealed itself subtly — bits of floating twig and moulted willow fluff slipped by on its surface at a quick walking pace. After pushing off it took some mighty strokes to get the kayak diagonally across the river. Then I was Immediately passing under the gangly Victorian structure of Staines Railway Bridge, where I could see back waves rising up off its piers and hear the rushing gurgle where the water sucked at the air as it swept around them. There are a couple of live-aboard Dutch barges and narrowboats moored abreast off the bank just below the bridge, and I quickly paddled back towards the centre of the stream to avoid being lodged nose-first between two riveted iron hulls.

|

| Boats moored on the River Thames at Staines |

The surface of the Thames below the bridge rose glassy and convex, as if something huge was about to surface. The whirlpool was turning slowly like a pot of heated water just before the chaos of boil and I marvelled at this vast, smooth disruption. My bow slipped into the swirl and immediately shifted right. I cut my paddle hard on that side and the boat skimmed straight across.

Left unpaddled — abandoned to the river, as it were — a kayak (and most boats) will drift at right angles to the bank and carry on downstream. And this is a fine and effortless state of affairs to indulge on a lazy sunny day when the current is weak and there are no other boaters about. When the current is brisk and at your back, it is a constant challenge to keep the bow pointing downstream so that the kayak remains stable and presents a much narrower profile to such obstacles as moored barges, shallow banks and low hanging branches. The Thames is famous for its willows, and in high water tangles of their branches will appear lower and there will be many more of them combing the river.

I soon found myself on that beautiful, suburban stretch of Staines where long, tailored back gardens stretch down from substantial homes to the river’s edge. This being Saturday, a few of their inhabitants were reclined in loungers enjoying the morning sun over tall glasses of orange juice and newspapers. Kayaks can be very intimate vessels — low in the water and utterly quiet except for a light, almost hypnotic, splish ... splash ... splish ... splash of the paddles. Hugging the bank I suddenly entered the snug morning worlds of the breakfasting newspaper readers. We would be a couple of feet apart, within easy speaking distance of each other. It is a pleasant fact that in the English river world, and especially at this human, unmotorised scale, the instincts of most people is to smile, give a small wave or tiny nod, or offer a gentle ‘Hello’. If my hands weren’t busy paddling I would have tipped my cap. I experienced a quick succession of these sunny visitations: unguarded dreamlike moments of warm goodwill.

|

| Motor cruiser beneath golden willow trees on the River Thames near Staines |

One man, relaxing with his wife at the bottom of their garden, smiled over his Telegraph and we exchanged acquaintances. ‘Nice day for it’, he said, then a soft caution, ‘Stay away from the weirs’. ‘Yes, thanks’, I said and waggled my paddle good-bye as I flowed on. This brought me up sharply though. Good advice, as the raucous weir that tumbles over the neck of Penton Hook — that now navigationally redundant loop of the Thames bypassed by Penton Hook Lock — was close to hand.

I passed a fellow muscling the long oars of a traditional, clinker-built rowing skiff upstream. He seemed to be just barely making headway against the far bank. My task, in comparison, was much simpler: dip a paddle to keep my course; paddle rhythmically for bonus speed. In the swift current I seemed to be travelling some three times faster than normal.

Penton Hook Lock was yellow-boarded with warnings about the speed of the stream. As I floated in the chamber the lockeeper told me that so much water was going over the weir that there would only be an 18-inch fall in the level of the lock. He also warned me that one of the cruisers waiting to enter from downstream was struggling with the current, zigzagging about at full throttle. A couple of minutes later I was gliding between the opening gates and out into a very quick stream coming off the weir and from around the Hook. I was just beginning to be able to read the river surface and calculated a path that put a series of glassy-topped whirlpools between me and the slippery cruiser.

When I’d set off that morning, unaware of the usual river conditions, my plan had been to paddle upstream towards Penton Hook Marina then cut left to explore the ‘secret’ Abbey River backwater that only a canoe or kayak could penetrate. But the current was so powerful that five minutes paddling my gear-laden kayak saw me no better than 100 feet upstream. Why fight it? The day was suggesting distance and speed, so I quickly sought thrill over exploration, swung the kayak around and swept back into the flow of the Thames towards Chertsey.

|

| Fly deck motor cruiser on the River Thames |

Chertsey weir is long and angles out diagonally from a headland, forming a sort of funnel to Chertsey Lock hard on the opposite left bank. The whitewater boiling below the weir was tremendous. Large houseboats on the far shore were bobbing about like tethered corks in its wake. Because this navigable funnel is narrow there was a strong draw across it. I held to the left bank, raised my awareness and paddled strongly. To find yourself midstream here in a lightweight boat, even with a small outboard engine, would probably be to find yourself being swept over the weir and churned into the dancing whitewater.

About two-thirds of my way across a 40-foot motor cruiser pulled up beside me. From the fore deck, towering 15 feet above, the silhouette of a woman against the sun bellowed down, ‘Sorry, we can’t slow down here!’ Or words to that effect — I couldn’t hear everything over the sound of crashing water. Then yelling back again, ‘Sorry about the bow wave ... Sorry!’, as I hit three massive waves, slapping over each as directly as possible. Then the boat’s twin engines churning the river as it passed.

It is almost unheard of to be overtaken by another vessel on the approach to a lock and I was completely surprised by the cruiser’s appearance. Both large and small craft usually drift slowly, slowly towards a lock, form an orderly queue and wait for the gates to open. But having recently priced some serious boats, I wouldn’t have slowed either. There is no way I would risk £180,000 of cruiser going into or over the weir. But, from the vantage of a high fore deck, I might have looked well ahead, spotted a bright orange kayak, and calculated my passage accordingly.

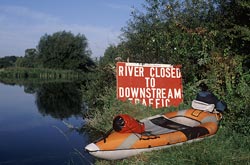

Chertsey Lock, and all subsequent downstream locks, showed red board warnings. The Environment Agency’s yellow and red board warning system indicates the strength of the stream and the related risk to boats, especially unpowered ones. Yellow boards recommend that unpowered craft don’t navigate and powered craft navigate with caution. Red boards recommend that no boats navigate. The system is for guidance, and decisions to boat or not fall on the shoulders of those boating. At no lock did I meet with anything but a cheerful welcome and some chat about the unusual conditions. One or two lockeepers seemed a little envious.

The sturdy stone piers of ancient Chertsey Bridge gave rise to even more extensive whirlpools. No barges here though, just a wide curve of the river bounded by an expanse of meadows to the left and new, port-holed designer flats to the right.

On a normal current, arriving at Shepperton Lock would have marked the end of a good, full day’s paddling from Staines. It would have been approaching 6pm and time to pull Little Wing out of the water, fold her up (for she is an inflatable craft of hi-tech German rubber wrapped in a streamlined nylon skin — see Kayak Photography article), and bundle her off to Shepperton rail station on her collapsible trolley. On the fast current, though, I pressed on and decided to have a late lunch of brie and chorizo sandwiches opposite Shepperton’s public moorings, suspended on the river beneath some friendly willows.

Savouring a block of dark chocolate, I mused on the dozens of water borne bugs, with their one-inch wing spans raised like tiny sails, that drifted on the current around my kayak. For these insects the small standing waves that rose past my bow were not unlike the waves of the cruiser I’d fought above Chertsey weir. Unlike kayakers, though, the bugs seemed to happily give themselves up to the current, taking a jolly tumble as they went by, but somehow staying buoyant and dry.

|

| The Anglers riverside pub at Walton-On-Thames |

Recharged, I paddled on. Walton-on-Thames, with its riverside pubs swarming with people, slipped quickly by. Another crowded pub above Sunbury Locks. In the lock I chatted about canoes and currents with the lockeeper. She told me that it takes about three days for rain falling on Lechlade — the navigable head of the Thames — to reach Sunbury. I guess that’s how long a water bug would take to float the distance. If it were so inclined.

I passed a cluster of dinghy sailors off Phoenix Island. In series they blew into the current behind me, their starchy sails crackling in the wind that had begun to rise from the northeast. These are not serene craft, and their occupants — either solo or in pairs — were in constant motion manipulating the sails, ducking booms, splendidly arching their backs over the severely bevelled hulls to counterbalance the wind. Giant navigating bugs. They were having a terrific time zigzagging down the river at speed, half of them nimbly overtaking me within the next reach.

At Hampton I chose the quick stream around Tagg’s Island, heading straight at the upper weir, then turning right at the last moment for Molesey Lock. The island is home to a variety of houseboats, many of which, from a distance, look like nice suburban homes. When viewed close up, though, you see they float on purpose-built steel barges. Glass sliding doors open onto the river and allow the paddler a glimpse of all the accoutrements of a consumer life: 50-inch televisions, slender oak dining tables, white woollen carpets and playful, wall-sized painted canvases and sculpted works of art. Some homes have a nifty little speedboat parked in a mooring bay beside them. Secured amongst them was a wonderfully eccentric giant metal pod, a steel carapace brought up 20,000 leagues, with exposed bolt heads outlining its steel panelling and gaping portholes.

After skirting the more traditional jumble of live-aboard narrowboats and barges of Ash Island — whose eccentricities were expressed through varnished bowsprits, Auvergne style window shutters and forests of potted herbs — I negotiated the main weir and entered Molesey Lock with three lads in a listing 12-foot power boat. A few hours earlier, when I had been lunching and lounging opposite Shepperton, they had roared by me waving long-necked beers. They were much more sedate now, operating a portable bilge pump and dispensing water in sharp squirts over the side.

|

| Dark clouds and illuminated boats on the River Thames |

Passing beneath Hampton Bridge I seemed to enter a different world. Here the sky was mottled a dark pigeon grey and a fierce upstream wind had risen causing the quick river to become choppy. Henry VIII’s magnificent Hampton Court loomed low on the left bank. A large tour boat was moored below and small pink faces and gesturing arms crowded the decks. Music rose out of the park beyond and the gold ornamented gates of the Pirelli Garden dully gleamed. This would be my final stretch to Kingston Upon Thames.

Below Thames Ditton the channel narrows and I could see the surface of the water rising dramatically around each bow of the many dutch barges moored along the stretch. There was also more boat traffic. I now had to re-align myself to cut through two-foot swells in the wake of motor cruisers punching their way upstream, then quickly swing the kayak 70-degrees to tackle the echo waves rolling off the towering stone bank walls. At a crook in the Thames, where a collection of British Waterways working barges was collected, the river looked deep, dark and oily. From here all the way into Kingston I rode straight into foot-high rolling waves. This was exciting work and a great finish to the voyage. I felt part of a movie when some low golden light appeared at my back from beneath the cloud and illuminated the rythmic spray of water blowing off my bow each time it broke through a crest. I was toasted with champagne flutes by a wedding party lolling about on Ravens Eyot as I battled past. The world was my oyster.

At Kingston I could see the public moorings ahead were inundated, so sidled

up to the low landing stage of a sailing club and pulled Little Wing

out of the river. It had been a terrific run: 14.5 miles (23.5 km) from Staines

to Kingston through five locks in under six paddling hours (ignoring the floating

lunch). Not bad for an inflatable kayak ballasted with camera equipment, spare

clothing and boating gear. I hadn’t taken a single photograph, but it

would have been foolhardy to put the paddle down for a second. No sense losing

it to the current, or seeing my camera do service as a boat anchor.

Jim Batty

jimbatty.com

Text and photographs copyright © 2009 by Jim Batty. All rights reserved.

No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, without signed written permission from the author. A standard publishing fee is payable in advance for any editorial or commercial use.