Local Wanderings in NE Thailand

Sure enough, I found the famous welcoming warmth of the Thai people a wonderful balm after a lengthy journey through Pakistan and China. And I had developed a little more sense of who these people behind the smiles were by travelling into northern Thailand and setting out on a Hill Tribe Trek from Chiang Mai. But there was still a barrier between us which I found difficult to breach — a sort of ‘glass wall’ thrown up by a highly developed tourist industry that makes it far too easy to indulge yourself. I needed a release from the distraction of Riley’s professional snooker hall, where the girls hand you a rake with attention and bring cold beer on a nod. To get away from the hundreds of sandwich boards (promoting trekking agencies) that littered Chiang Mai’s crowded streets. To go beyond February’s Flower Festival. Being a romantic, I wanted to wander in Thailand’s small and mysterious places ... and sleep in a house on stilts.

On a gleaming nickel-plated bus, in 99-degree heat, I set off for Thailand’s northeast — beyond the Dong Phaya Yen mountains where clouds scraped the peaks and mist dangled down like creepers into the damp forests. East of this natural barrier, foothills poked up from a dry plain, splendidly isolated from each other, leaning this way and that like bactrian camel humps.

Loei appeared amongst the humps, a modest frontier type town full of truck repair places and inexpensive clothing shops spilling out onto its crumbling streets. Despite it being Friday night, as evening approached the streets became deserted. Simple habit drew me into a rustic billiards hall sporting four tables, their baize tops patched with bookbinding tape. The family who ran the parlour were all snuggled into low chairs below the bar counter watching a snowy screened television set and munching snacks.

After a brief chat about local hotels I stepped out into the night. A man on a bicycle, carrying an iron shaft with a large ring on its tip, came at me from out of a dark alleyway. I stepped aside and he whispered past. Bizarrely, he stopped at a lamp post and clanged his implement against the metal cable supporting it. Two quick clangs, a short break, then two more. He repeated this four times, then cycled off to another post and did the same. Then he went to a lamp post bearing a suspended ring and ritually hammered that. I chased after him to question him with pointing, shrugs and mime, but he simply smiled at me and pedalled off. Here was another fleeting aspect of travel which was to remain unexplained.

A songthaew (meaning ‘two rows’ in Thai) is a truck with the proportions and frame of an Africa overland type vehicle stripped to its basics and offered as public transportation. Climb up the back of its decoratively welded rear steps and you are likely to be confronted with at least a dozen curious faces belonging to local farmers, market stall owners and Buddhist monks. The crowd sits on two benches running the length of the truck’s bed opposite each other. Usually a great assortment of rice sacks, cardboard boxes of melons, dumb-eyed chickens tethered with strings and woven baskets the size of golfing umbrellas jostle at the passengers' feet. You quickly become a welcomed part of this group and intimate life dramas unfold as you bump through the countryside from village to town to village. On one occasion, the woven hat of a simple country woman blew off her head as we pulled away from some obscure stop. The woman, too shy and good natured to say anything, just smiled and instinctively reached out towards her hat, with its pretty blue band, settled in the orange dust and growing smaller behind us. Almost as one we hollered out for the driver to stop, then grinned at each other as the truck began to reverse down the track to retrieve it.

The balcony of my guesthouse in Chiang Khaen overlooked the Mekong River (Mae Nam Khong). Here I reclined for two weeks, gazing at an outpost of Laos opposite, waiting for the cocktail coloured sunsets that lasted as long as feature films. One evening I was invited to a wedding banquet, layed out on a mass of tables overtaking the village’s two main streets. Early into the feast a five-man Thai rock band appeared on the back of a flatbed truck. After rigging up their amplifiers and lighting system, I had the rare opportunity to dance and flirt with the eligible young women of the village.

Prying myself from the guesthouse family, I hitched a lift one morning to Pak Chom, a few miles eastwards and downstream, with a short, wrinkled man in a Toyota pickup. On our journey an ambulance came abreast of us on the twisting road and we stopped dead centre to have a chat. Later the driver explained to me through sign language that he too was an ambulance driver for another local hospital and that they had stopped to exchange news. As if to illustrate this explanation, he put his foot down to the mats of the Toyota and we roared along the shimmering river road abusing the white centre line. To make conversation, he pointed out and told me the Thai word for every variety of fruit tree we blew past — papaya, coconut palm, banana, mango, ...

In Si Chiang Mai I stocked up on some oranges bought from a woman in the market who grinned a full set of polished black teeth! Could they have been made of ebony? Further east, the only available hotel room in Tha Bo oozed the sweet, damp funk of a place normally rented out by the hour. I escaped south on a private flatbed truck, which dropped me off beside a brickworks in open country at dusk. I planned to try and pitch my small tent somewhere discreet for the night, but the driver wouldn’t have it. He flagged down the next vehicle to pass on the road, a motorcyclist, and gave him instructions as to what to do with me. This became my first of many motorcycle rides in the northeast, where I regularly found myself clinging pillion and developing previously untrained back and thigh muscles supporting my bouncing rucksack.

I was driven to a rural training college and put into the hands of a teacher who lived with his wife and other married teachers in a pleasant little enclave of houses set in a wood. As the next day was a Buddhist holiday, half a dozen male teachers relaxed around an outdoor table celebrating and drinking Mekong whiskey mixed with ‘electolyte’ fluid. Well after dark we all shifted to straw mats under the trees for dinner, taking our shoes off before squatting. The Thai language teacher’s wife appeared amongst us long enough to serve bowls of spicy soup and pots of heavily chillied meats and vegetables. We ate from the communal vessels with a combination of spoons, fingertips and hand-rolled balls of the glutionous ‘sticky rice’. Much later, the man’s wife made a brief comment to me in perfect English. I smiled in amazement and tried to draw her into the group. Not wanting to upstage the men’s party, she ominously said in English, ‘Less talk, more drinking’ and disappeared for good.

Conversation at the party weaved in and out of sensibility. The English teacher, playing interpreter, was by no means fluent (or sober), but through him I did learn from the Art teacher of an ancient cave in the district that was apparently full of artworks. I shortly thereafter excused myself, dropping from fatigue and firewater, to slip under the woven blanket of my host’s spare plank bed.

Erawan Cave was quite a bit further off than I’d understood the Art teacher to suggest and involved a couple of buses, a songthaew and a lift as the third man on the back of a Yamaha 125 motorcycle. The landscape surrounding the cave was a surreal collection of scrub-covered knobs and saddlehorns of rock thrusting out of the cultivated tableland. I mentioned to the two motorcyclists that it looked perfect for camping in, but the driver said it was dangerous to sleep in the hills because of animals: ‘Tigers, bear, many snakes. Cobras!’

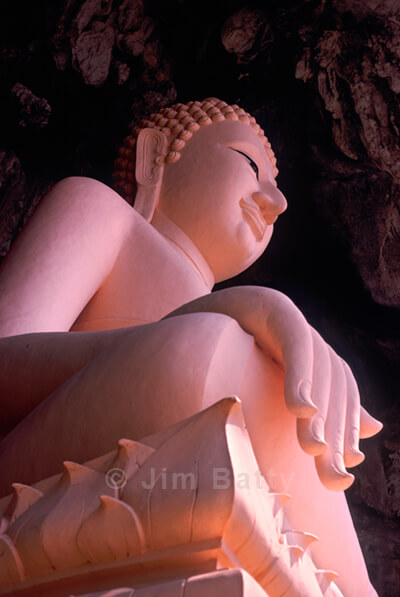

Erawan is the God of Artists and in this particular incarnation he stood as a three-headed elephant statue at the foot of the steps which wound up to the cave. The cavern itself was gigantic, much more a hollow mountain, and at its mouth squatted a huge, peach-coloured Buddha. In the roof of the upper cavern — perhaps 300 feet up — was a small, oval portal that formed a cycloptic eye on the sky. Curiously, the quality of the meagre light inside fluctuated between blue and red as clouds floated over. Birds chirped and echoed up in the greater blackness while I siesta-snoozed on a stone shelf in the natural airconditioning.

A string of neon tubes atop posts lead steeply downwards to the bowels of the cave. In a side hollow I found stalactites that had descended and met up with stalagmites to form natural stone chords connecting ceiling and floor, which sang in low musical tones when I thrummed them with my fingertips. I could detect no man-made artworks or paintings, but I could have easily misunderstood the whiskey interpretations of the night before. In the late afternoon the few Thai visitors to the cave had left and all was quiet. I decided to spend the night in the cave and, cradled at the giant Buddha’s feet, I was able watch a pumpkin orange sun set through a haze that enveloped the landscape. Farmers had set their slashed fields below on fire to burn, and slowly the low flames expanded across the plain and formed fiery jagged crowns atop the lumpy hills opposite in the night. I slept at the Buddha’s back.

Large buses with open doors and sound systems blaring Caliba’s Thai-rock music carried me further east. Ban Chiang is an important archaeological site with remains dating from about 3000BC, and is home to an ancient and stunningly beautiful, ochre on cream, whorl pattern pottery. Despite having a small but world-class museum developed with American funding, Ban Chiang is little more than a village. Taking local directions, I searched out a certain noodle stall and asked its proprietor if I could stay with his sister’s family for the night. When I arrived at the family’s home, her husband was embarrassed by my presence. ‘This is not as good as you are used to,’ he said of their clean but bare wooden house — a wooden house on stilts. I convinced him it was absolutely perfect and agreed to pay them a small amount of Bhatt for the night’s stay. Mosquitoes invaded as we sat in a circle on their front porch around communal dinner bowls. The meal was meagre and included a spindly, plucked and roasted bird the size of a sparrow, shot that afternoon. From simple hunger they self-consciously hoarded the bird for themselves, and I felt like I was pinching food from their children’s and in-law’s mouths.

That evening I bedded down on a folded blanket in a dark room. I asked if they had a mosquito net I could use, as the insects were now out in force. The husband said ‘no’, but his wife nodded yes, and I felt a heel when she came back with a stiff, new, double mosquito net from their one storage cabinet. Next morning I awoke on a floor of thick teak planks worn smooth with use. Beside me stood a pair of 3000 year old clay pots — near perfect specimens, like those inside glass cases in the Ban Chiang Museum. These two, collecting dust, would be sold to ‘some men from Bangkok’ for £2 apiece.

Working my way down through a very rural district of the Mekong yet further east, my songthaew completed its run at Chanuman. As I slurped down a bowl of pork noodle soup at the roadside market, someone threw their arms around my neck from behind. Smelling alcohol, I was not amused and I shoved the drunk off of me. As he swaggered over towards some giggling market girls I noticed he was wearing the type of black leather boots usually only worn by the police and military personnel. Twenty minutes later, on the edge of town where I was standing in the shade of a tree hitchhiking, the policeman reappeared on the back of a commandeered motorcycle to interogate me. He stood much too close for comfort and we eyeballed each other through our respective sunglasses. I backed off and took note of the handcuffs on his belt, while he no doubt enjoyed my trembling attempts at communication and supplication. Miraculously, he suddenly got back onto the bike and ordered the driver back into town.

I was very relieved to get a quick ride in a pickup truck with six local men — all of whom had thickly calloused feet with widely spread toes that fanned over the sides of their rubber sandals. One man pointed to a crazed, dizzy woman travelling with us and made a joke about ‘marijuana’. My spine crawled at the word as I envisioned that black-booted, unmarked policeman overtaking us on a motorcycle and planting a little bag of weed in my pocket before making an arrest. Not unheard of in Thailand. I now decided to leave the Mekong border areas and re-enter the northeast hinterland.

At 5.57am, I was awakened in my tent by the rasping buzz of every male cicada — of which there were thousands — in the bush. The effect had the impact of a live chainsaw set down on my pillow. In twelve minutes they had finished and the tinder dry forest became dead quiet again. The obscure and remote cliff face of Phu Pai Lai revealed itself to me as a gash above the trees. This was one of those places lost to all but locals and those foolish or curious enough to be drawn by unusual markings and symbols on maps. Somewhere near here was preserved a variety of prehistoric art.

I picked up a trail along the foot of the cliff. After some distance I came across a monk and a layman alone on a projection of rock building a teakwood staircase. A stairway to heaven? They directed me upwards, and I scaled the upper face with swinging pack and shoulder bag on their primitive bamboo and rope ladders. Concealed on the spacious ledge above sprouted a couple of wooden board huts and a tiny, balconied Buddhist temple. A young smiling monk welcomed me — they rarely seem surprised at anything — and afer a little mime talk, lead me to a natural gallery in the rock face which was protected from the elements. He pointed out some of the frogs, squirrels and human forms engraved into the cliff some 3500 years ago, while the lyrical chants of an older monk began to issue from the little temple behind us. Later we sat quietly on the balcony to eat that morning’s alms — sticky rice, chillied vegetable greens and tinned sardines — and contemplate the endless bush below. A blue-eyed temple cat, with a tinkling bell around his neck, joined us. We both preferred the sardines in tomato sauce. This ledge was as far from Riley’s snooker hall as I could imagine.

Jim Batty

jimbatty.com

Text and photographs copyright © 2021 by Jim Batty. All rights reserved.

A version of this article was first published in Globe (UK; Jan-Feb 1989).

Feel free to link to or share this page. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, without signed written permission from the author. A standard publishing fee is payable in advance for any editorial or commercial use.